The History of Physical Education

Where PE Actually Came From

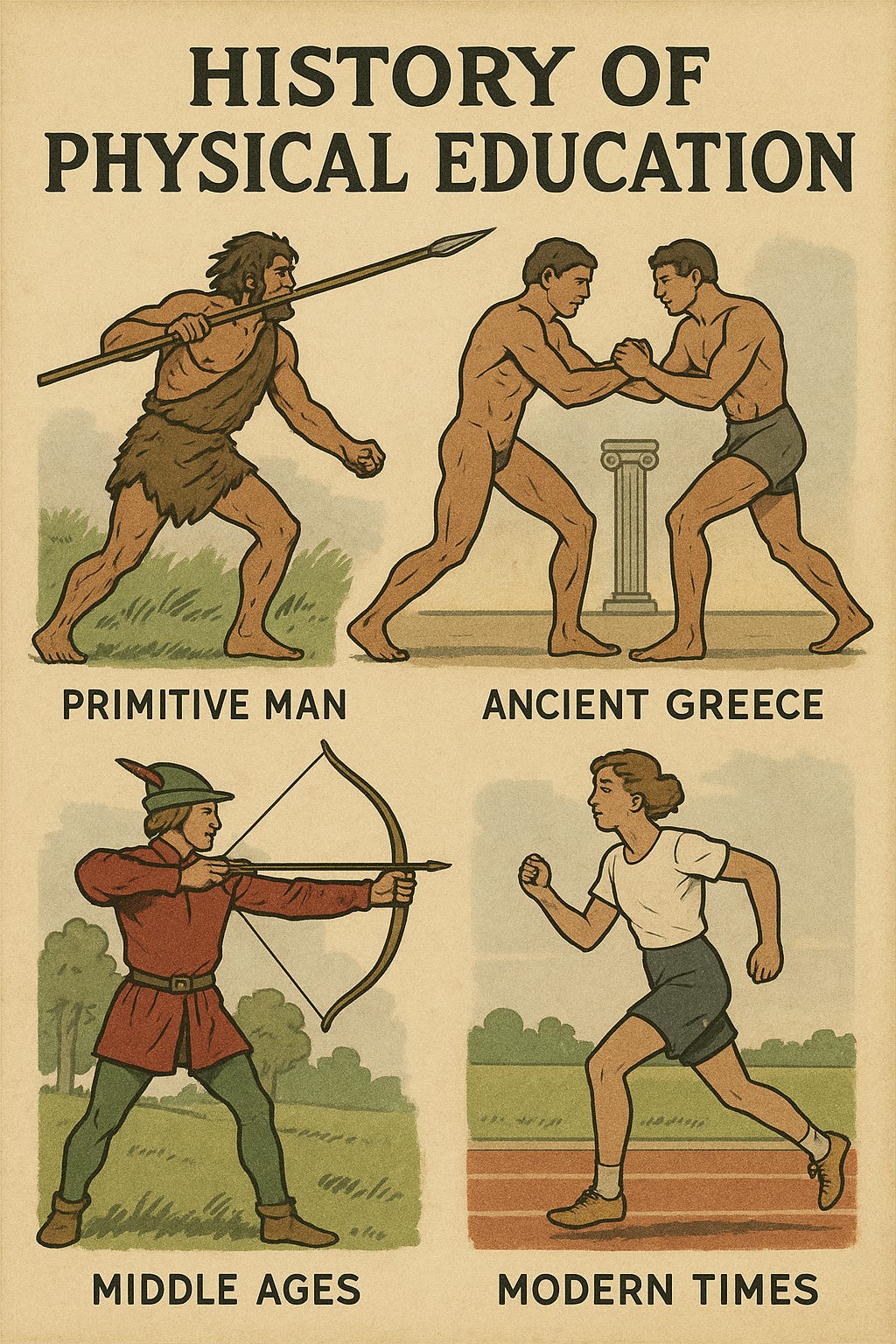

Archaeological evidence suggests early sports may have started around 13,000 BC. Deep inside the Lascaux caves of France, paintings around 15,000 years ago depict figures engaged in running, jumping, and other ritualistic activities. The Altamira caves of Spain showcase figures throwing spears in what could be interpreted as a game of chase dating back 11,000 years ago. In what we now call the state of Oregon, archaeological evidence of running sandals from over 9,000 years ago show wear patterns consistent with long-distance running. The Kakadu National Park in Australia shows indigenous rock art of figures throwing sticks for gameplay from around the same time. While some of the archaeological evidence mentioned above could be interpreted as depictions of hunting instead of sport, physical activities such as running, jumping, dodging, and throwing were integral to prehistoric life.

The ancient Mesopotamia civilization shows clearer evidence of the athletic competitions of archery, wrestling, and chariot racing around 5,000 years ago. In Egypt, there are tomb paintings and hieroglyphics depicting a variety of physical activities, even swimming, which included spectators. The most convincing evidence of early spectator sport dates back to a little less than 3,000 years ago, where ancient Greece attracted large crowds for the Greek Olympics. Around this same time, the Roman Games put on the very popular gladiator games. While these early competitive activities might have been rooted in ritualistic practices showcasing skills for warfare and hunting, over time, the competitive and entertainment aspects became more prominent--suggesting the establishment of spectator sports.

We can draw some conclusions here. One, there must have been some kind of physical and skill-based training happening. In fact, about 2,800 years ago, ancient dumbbells called “Halteres” were used for weightlifting. Before dumbbells, there are wall paintings of other activities like jumping stones and platforms. Depictions are shown of people jumping over and on top of obstacles–likely for the purposes of exercise. With all of this evidence of physical and skill-based training, what did their training programs look like and what were the qualifications of the person who taught it?

Tracing back the exact origin of sport is challenging because it involves piecing together fragments of evidence and interpreting social behaviors from a very long time ago. However, as we get closer to today, we have some concrete evidence of physical training education.

Around 400 BC, Plato spoke about the physical training of Sparta in his dialogues Laws, Republic, Protagoras, and Laches. Plato saw this kind of physical training as essential for military preparedness and believed it fostered mental benefits as well. Plato never visited Sparta himself and probably only heard of the Spartan physical training through other written accounts or the exchanging of embassies. For the purposes of this discussion, we will call Plato’s recollection of the Spartan’s military-based physical training Physical Education 1.0.

Plato’s dialogues were renowned because of his comparative explorations. He compared various elements of life because he believed in an ideal form of everything. Plato believed in a state-controlled education system where physical education was compulsory for all citizens, regardless of social class or biological sex - which was in direct contrast to the more privileged-based, male-dominated Athenian education system. While most Eastern physical education practices, like yoga, have linked the body and mind three thousand years before Plato, much of the writing from back then has yet to be fully deciphered. Plato’s writing about how a healthy body created a healthy mind is where we will consider physical education 2.0 started.

Unlike the Spartans' brutal and sometimes deadly physical training of Physical Education 1.0, Plato advocated for moderation. He believed moderating training intensities would prioritize long-term health and prevent injuries. His ideal form of physical education would be to help students find a balance between physical exertion and intellectual pursuits of how to move better. Rather than solely relying on military-based drills and war-based exercises, Plato - at least among today’s scholars in the field of kinesiology - became the first person to envision physical education as a form of education itself. He even proposed activities like wrestling and dancing could promote ethical qualities like courage and fair play. Plato’s proposal here shows how social and emotional wellness was connected to his version of physical education.

Plato envisioned Physical Education 2.0 could help develop a virtuous society by creating citizens who were not just physically strong, but also capable of contributing meaningfully to the republic. He foresaw how Physical Education 2.0 could create a sense of unity and social cohesion among all the social classes while still creating mentally and physically strong citizens who could better defend the republic.

Well after Plato, during the Middle Ages almost all aspects of education centered around practical forms of physical activity like hunting, archery, and horsemanship. Physical development was primarily acquired through daily activities and games rather than any formal education systems. It mostly centered around the “soul.” It’s thought that during this time the ideas about fairness, honesty, and concern for others were developed. Medieval tournaments became popular displays of skills and strength with the unique addition of chivalric ideals such as codes of honor. Even though injuries and death were common during these competitions, there were strict rules governing gameplay such as preventing undue harm to your opponents. Social wellness ideas, like etiquette and fair play, dominated most of the culture.

Between the 14th and 17th century, during the Renaissance, a revival of classical ideals in ancient Greek and Roman culture re-emerged. Athleticism and physical fitness regained a higher level of importance as compared to the Middle Ages and books on the importance of physical education as a way to develop well-rounded individuals were published. Leonardo da Vinci and other thinkers of that era started to study human anatomy and movement, which laid down a foundation for a more scientific approach to exercise.

In the late 18th century, Benjamin Franklin promoted the idea of lifelong learning and personal responsibility through intentional movement. Like Plato, he believed in the connection between physical activity and mental health and even promoted the idea of good sleeping habits. He had a particular interest in swimming and horseback riding and encouraged others to find forms of everyday movement as a tool for self-improvement. Modern day fitness products such as dumbbells became more widely used during this time period as well.

The “Cult of the Body,” emerged across Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries as a way to promote physical activity through education. Medical advancements and a growing understanding of anatomy, physiology, and hygiene led to a growing interest in the human body. As physical education and health awareness continued to grow, the human body became commercialized through fashion, beauty products, and as a tool for self-improvement at the level of morality, physical hygiene, and self-control. During this period, there also was an increased amount of leisure time (for certain socioeconomic groups) which promoted the development of more organized sports. Prussia, or what we now call Germany, underwent an educational reform which included a greater emphasis on physical education; particularly a form of gymnastics movement system called, “Turnbewegung.” Around 1820, Freidrich Ludwig Jahn became regarded as the first ever physical educator who taught outdoor gymnastics and calisthenics in Germany. The reform advocated using physical activity to promote the holistic development of youth to strengthen the Prussian army and build disciplined and resilient soldiers. Around the same time in Sweden, Pehr Henrick Ling influenced the U.S. physical education system with a Swedish gymnastic system that centered around calisthenics and integrated anatomy, physiology, and circulation. Ling’s gymnastic system also played a key role in the development of a differentiated instruction based on students’ needs and abilities in movement coordination, posture, and physical development. His work on posture and movement coordination laid the foundation for movement analysis via biomechanics and exercise science.

Before the Civil War, the United States had a limited focus on physical education in schools. However, the development of the Round Hill School modeled our nation’s first educational system to formally have physical education play a central role in a student’s development. Round Hill was deemed to have an innovative pedagogy because of its departure from the traditional focus on rote learning and intellectual pursuits to a more holistic approach which included physical well-being. America’s first physical education program centered around German gymnastics called, “Turnbewegung.” Charles Beck, thought of as the first U.S. physical education teacher, taught his classes with ropes hanging from ceilings, walls built for outdoor climbing, and wooden horses. There was an importance of play and joyful movement in his classes, however, his instructional focus placed a heavier emphasis on uniformity and collective discipline rather than Ling’s more individualized instructional approach. Beck brought “Turnbewegung'' into the U.S. educational system in the 1830s and 40s, but it wasn’t until after the Civil War ended in 1865 that national military concerns over the physical fitness of U.S. soldiers reinitiated the need for physical education. In an effort to respond to this concern, Beck’s system of “Collective national fitness = national power,” became a foundational aspect to the U.S. physical education system at the time.

Physiologist Carl Ludwig and physician Etienne-Jules Marey created the groundwork for how the body responds to exercise in the mid-1800s. This knowledge influenced physical education curriculum, but had more of a focus on cardiovascular exercises and muscular development - or what we now call the “Health-related components of fitness.”

By the mid-1800s, individual states mandated physical education in public schools and by the 1880s a rise in organized sports influenced the content being taught in physical education. In 1885, the Association for the Advancement of Physical Education (AAPE) was established by the “Father of American Physical Education,” Dr. Edward Hitchcock Jr. a year later it changed its name to American Association for the Advancement of Physical Education (AAAPE) and held its first convention in New York. Meanwhile in the same year another organization formed called the “The Society of Directors of Physical Education in Public Schools,” which would later restructure and combine with AHPERD to become what we now know as SHAPE America. This organization recognized the need for professional teaching standards in physical education. The creation of movement science, later called kinesiology, pioneered the first analysis of different physical activities beyond the health-related components of fitness. The rise of kinesiology influenced physical education to adopt an additional focus of skill-related components of fitness and a biomechanics approach to motor skill development. In 1898, “The Society of Directors of Physical Education” organized the first national convention for physical educators which highlighted professional development and networking.

As the American public education system began to develop so did the importance of being physically educated. Because there were so few people qualified to teach physical education during this time, medical doctors created teacher education programs in the universities. Starting in 1861, Dr. Edward Hitchcock Jr., who was a professor of hygiene and physical education at Amherst College and founder of AHPERD, created the anthropometric measurements of his students (Height and weight; chest, waist, hips, and thigh girth; lung capacity; grip strength tests; leg lift strength tests; and posture assessment). He would then design an individualized fitness program for his students based on the measurements he collected. It’s important to note that since the 1820’s colleges had been hiring physical educators, but Dr. Hitchcock Jr. is credited as the first physical educator at the collegiate level due to his innovation in the field of health-related fitness and creating fitness plans and protocols. In fact, he is nicknamed the “Crusader for Fitness.”

Dr. Dioclesian Lewis founded the Normal Institute. The Normal Institute was the very first teacher education program for physical educators in the United States. He also wrote and taught a lot about the physical culture and the importance of lifelong physical activity through his new “Gentlemanly Gymnastics” system for men, women, and children. His system was designed to focus on flexibility and grace rather than raw strength.

Dr. John Dewey’s contributions to physical education were that knowledge should be practical and applicable to real-life situations. According to Dewey, play of any kind was a natural form of learning for children. His writing and teaching focused on how playing could help students’ problem solving skills through exploration and experimentation; social skills through interaction and cooperation with others; imagination and creativity through self-expression; and, of course, physical skills through movement and exploration of skills in gameplay. Many of the newly released standards by Shape America in 2024, show how Dewey’s influence still remains prominent today.

Delphine Hannah was hired by Oberlin College in 1885 where she created the first physical education department at the college. Not only was Delphine considered to be a pioneer in physical education for women, her work further established physical training as a legitimate academic discipline within colleges and universities.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, the rise in popularity of sports influenced more sports-based education physical education programs across the United States. The United States became the first in the world to include sports at the collegiate and high school levels. Most historians credit Harvard and Yale intercollegiate rowing matches for capturing public attention and interest in sports. Sports were taught as a way to get exercise and it gradually dethroned gymnastics and calisthenics as the model of physical education programs.

American Football was thought to have originated in 1860. By the 1880’s, American Football coaches became the American Physical Education teachers. This led to many curricula where football drills and football training methods were the focus. In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt and the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (IAAUS) had to step in to regulate safety protocols of American football as injuries and deaths while playing the sport increased at the elite universities. While there were many safety protocols put in place, one worth noting is the legalization of the forward pass. By 1910, the IAAUS sought a more descriptive name that reflected the organization's national aspirations -- changing it to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA).

Alexander Cartwright invented “roundball,” what we now know as baseball. Baseball became immensely popular in the late 19th century as the United States came up with its first unique sport involving striking with an implement.

In summary, teaching of sports in physical education programs took a while to catch on, but gradually fitness-oriented, gymnastics and calisthenics-based physical education programs shifted towards activity-based learning for student enjoyment. This eventually marked the birth of fielding games in physical education programs which would later lead to physical educators being responsible for teaching positive social interactions such as sportsmanship, moral values, etiquette, fair play, teamwork, and strategy-building.

While the invasion game of soccer has a hazy origin story from the ancient civilizations of China, Greece, and Rome -- basketball was created by James Naismith 1891. Naismith was a young physical education instructor at the YMCA at the time looking for another type of invasion game that students could play indoors during the cold winter months in Massachusetts. He also wanted to find something that was less injury-prone than American Football. For the inspiration behind the creation of basketball, Naismith credits a children’s game called “Duck-on-a-rock,” where players attempted to knock a rock off a designated spot, and soccer for helping him design the game. For basketball, he wanted to create something like an indoor soccer game, however, he did not want players to be able to run with the ball. This rule proved to be too difficult to enforce. Consequently, dribbling emerged as a way for players to move with the ball. While basketball isn’t the first game to incorporate dribbling, its tremendous rise in popularity highlighted dribbling as a core skill to play the game.

In 1895, William G. Morgan, after seeing that some of his members found basketball to be too vigorous, created a game called “Mintonette.” Morgan’s game separated two teams of players by a net, where the objective was to volley a ball back and forth, and the concept of scoring taken from badminton. Professor Alfred Halstead, who witnessed a demonstration of Mintonette suggested Morgan rename it to be called Volleyball.

In 1906, AAAPE joined forces with the Playground Association of America and a year later “The Society of Directors of Physical Education” changed its name to the “National Society of Recreation and Play Officials.” Both name changes in each organization marked the importance of leisure play and recreation activities alongside physical education.

1917, Physical education became an important part of education as it was required to take courses in physical education at the universities and in public schools. This time period saw a surge in industrialization and concern about worker fatigue and its impact on safety and productivity. From the scientific curiosity of worker fatigue, David Bruce Dill – a young biochemist at the time -- joined forces with L.J. Henderson. In 1926, they created the Harvard Fatigue Laboratory – which became the pioneering institution of exercise physiology. Their research impacted many of the improvements we still see today in terms of worker safety, well-being, clothing, work schedules, and the importance of salt in sweat to prevent heat exhaustion. Even after the Harvard Fatigue Lab closed its doors in 1947, Dr. Dill and Henderson’s work still lives on in the exercise physiology and sports science fields. To this day, the Southwest Chapter of the American College of Sports Medicine includes a D.B. Dill lecture at its annual conference.

Around 1927, Thomas Wood, the co-founder of the “National Playground Association,” developed the first standardized physical education fitness assessments. Wood’s fitness tests were mostly aimed at elementary-aged school children. Physical educators implemented his tests and a “badge system” to award children who achieved specific skill levels in the activities of running, jumping, throwing, and climbing. The “badge system” was used to motivate, encourage participation in exercise, and to track progress in developing physical skills. Around the same time, Clark Hetherington, a leading advocate for a more science-based physical education, designed movement efficiency tests in an effort to establish more objective data in the field of physical education. The data collected from both of these tests promoted the idea of a data-driven approach to curriculum design for physical education.

In response to the growing connection between physical education and public health, by 1930, AAAPE merged with the Department of School Health of the National Education Association (NEA). But eventually, the Great Depression would cut nearly half of the physical education programs in public school from 1932-1934. Interestingly, during the draft of World War II, over a million young men were denied their ability to fight in the war due to poor fitness levels.

Post World War II, a surge of research in the fields of sports science and exercise physiology emerged and the requirement of physical education regained traction in public schools. Hans Selye’s work on stress and adaptation in aerobic training had a direct impact on the methods of athletic training and development in physical education programs. Selye’s “General Adaptation Syndrome” created the framework for interval training, cross training, overload principle, and mindfulness training we see in physical education today. The drive in all disciplines of education, but especially physical education, was to help create “good citizens” and sport became a fun way to help promote values and physical activity in physical education classes.

From these teacher education programs, three different perspectives on how to teach physical education to create good citizens emerged:

Jesse Feiring Williams

Jesse Feiring Williams added an additional goal of physical education to develop character and the soft skills that highlight morality. After his experiences as a coach, physical activities leader, and eventually a physical educator for the New York Institute of the Blind, he earned his medical degree. He saw a clear distinction of the two different perspectives of physical education as either education of the physical or through the physical. Education of the physical was the familiar perspective whose supporters promoted the idea that the best outcome of a good physical education class was strong muscles and ligaments. However, he saw this popular perspective as a narrow view of physical education should be and blamed the “Cult of the Body” for popularizing this point of view. Williams believed in teaching the whole person through the physical. He saw physical education as a way of living and when it was taught right, could help students live a life beyond the commonplace to the spirit of wholesome living. He taught physical education through the physical by creating a biological connection with body and mind and that physical education lessons could help students cultivate the loftier virtues such as: courage, strength, endurance, natural attributes of play, imagination, joyousness, and pride. After authoring and co-authoring over 41 books in thirty years, his physical education teaching theories became the most popular teaching philosophy during the 1920s through the 1940s.

Jay Bryan Nash

Jay Bryan Nash saw the focus of physical education should focus on the skilled use of leisure time that had specific objectives in lifelong physical activities. Nash was noted for being one of the top physical education thinkers of his time with a heavy influence on the sociological aspects of physical education. Unlike his classmate at Oberlin, Jesse Feiring Williams, Nash never went to medical school. Instead his background was in sociology and he became known at the AAHPERD conferences for how engaging his public talks were. He became the superintendent of the city of Oakland, California where they would be recognized as a model for cooperative use of city schools for physical activities, the number of and access to many playgrounds for kids, and the city motto Nash created for Oakland, “A playground within the reach of every child.” Nash co-authored the first physical education syllabus. His contributions to the field of physical education are many, but he’s credited for pioneering the cultural and sociological aspects of physical education with an emphasis on the self-selected activities of recreation. He believed teaching students in physical education about the emotions of others and collaborating with others would help develop healthier personalities in students. He authored 15 books and countless articles on the sociological aspects of physical education and the importance of recreation and leisure activities.

Charles McCloy

Charles McCloy believed that if physical education only consisted of exercising, weight-lifting, and overall physical fitness that in and of itself would suffice. Granted, during this time it was thought that lifting weights would hamper athletic performance. So it’s important to note that his perspective fought against the current trends--even among athletes. Coaches everywhere during this time warned their athletes to lift weights as this would make them slower and less athletic. McCloy’s underappreciated contribution to the field of physical education is in how he, through his scientific investigations, created a huge shift in the public and scientific opinion on weight lifting. Every study he headed found that building muscle was beneficial for athletic performance. Later, McCloy criticized the current state of physical education being primarily centered around sports and games - which was to the detriment of muscular strength in his opinion. He pointed out how easy it had become for a physical educator to roll out the ball and become a referee to a game rather than to put the students through an exercise program for building muscle. While his solution to the problem of rolling out the ball might be looked down upon in Physical Education 3.0, one of McCloy’s contributions that made its way into physical education standards of today is the idea of functional strength–or fitness required for an occupation and daily living. Much of the work from the Harvard Fatigue Lab contributed to McCloy’s research here. He spoke with an unapologetic conviction, best captured with the quote, “Weakness is a crime, don’t be a criminal.”

In the late 1920’s, Margaret H’Dohbler pioneered the advancement of dance and self-expressive human movement into physical education. Though not a dancer herself, H’Dohbler created the first university-level dance education program for women at the University of Wisconsin. She challenged the physical education programs that heavily emphasized rigid drills, movement patterns, and calisthenics. Her approach to physical education centered around how movement could be used as a tool for self-discovery and expression. She influenced other physical education programs to adopt dance into their curriculum as a way for teachers to enhance their students’ physical literacy, coordination, and creativity.

The President’s Council on Physical Fitness was established in 1956 by President Eisenhower in response to legitimate concerns about the declining physical fitness of American youth after World War II. Research from the Kraus-Weber Report found that American youth were significantly behind European counterparts in physical capabilities. The President’s Council on Physical Fitness aimed to promote physical activity through public service announcements, educational initiatives, and partnerships with schools and communities. The rise of technology and suburbanization along with an increased focus on academics led to more sedentary lifestyles which became a national security threat in the eyes of our military leaders as the Cold War fears continued to rise. In the council’s campaign titled, “Fitness is America’s Future,” celebrities, mascots, and professional athletes promoted what is now the iconic, “Presidential Fitness Test.” The Council’s campaign had a deep-seeded impact on physical education curriculum that research studies, following decades of data, showed improvement in American fitness levels and participation in sports. However, the Council did face some criticism for its standardized fitness testing and its lack of inclusion for students with diverse abilities and needs. The Presidential Fitness Test, which officially launched in physical education programs in 1961, consisted of six exercises that were chosen for its simplicity of measuring physical capabilities. Sit-ups, push-ups, pull-ups, standing broad jump, shuttle run, 600-yard run - which would later become the infamous “Mile Run.” The physical educator was required to test every student and help them analyze their health and skill-related fitness scores into one of four different ratings: Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor. Students who scored high enough across all the tests qualified for the prestigious, “President’s Physical Fitness Award.” While the original tests were eventually modified and then fully replaced by later standardized fitness tests, the original President’s Fitness Test pioneered the first nation-wide, curriculum-changing standardized fitness assessment for American youth. This turned a lot of physical educators into fitness-focused drill sergeants.

Dr. Ken Cooper, regarded as the father of the aerobics movement, developed physical fitness tests and standards for physical education through his Cooper Institute. His initial fitness testing included: 12-minute run which measured the distance a student could run in 12 minutes and assigned student scores to an aerobic points system to categorize fitness levels and set personalized goals for improvement. By 1982, he created the FitnessGram physical fitness testing that tested aerobic capacity through a 20-meter PACER test where students would run back and forth to a cadence that got progressively faster. Additionally, students could do a run-mile test or walk-mile test where they recorded their times and measured their heart rate after finishing. A muscular strength test where students would do push-ups and curl-ups. Muscular endurance where students would hold planks or do wall sits for as long as they could them. Flexibility where students were evaluated through sit-and-reach tests and trunk rotation. And, the now infamous, body composition through body mass index calculations. Dr. Cooper advocated for health beyond aerobics and emphasized the importance of a healthy diet, stress management, and optimal sleep for a more in-depth, holistic approach to personal health.

Enacted in 1972, Title IX prohibited discrimination on the basis of sex in all federally funded educational programs and activities. Prior to Title IX, female participation in physical education and interscholastic sports was either inhibited or severely limited. Physical education for girls often focused on non-competitive physical activities like dance and calisthenics, while their counterparts focused on competitive sport development. Due to a lack of Title IX enforcement in the early years, female participation in high school sports has increased tenfold since the federal law was put in place. While challenges in the equality of opportunity for girls in sports are still present, Title IX has had a profound impact on the cultural shift of traditional gender stereotypes in sport and helped foster a more inclusive and equitable environment for student learning in physical education. In 1975, it was written into law that students with special needs were to have equal access to quality physical education as well.

In 1975, the National Dance Association became an affiliated member of AAAPE. Three years later, dance became officially incorporated into the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance (AHPERD). This was a pivotal moment where the growing recognition of the social and cultural roles of dance in physical education and personal health. During the late 1970s dance became a hugely popular form of physical activity, artistic and self-expression, and cultural engagement. Within this decade the U.S. established the professionalization of dance education with teacher certification standards.

President Regan established the National Commission on Excellence in Education to analyze the quality of American public education. After two years of research, the Commission’s report titled, A Nation at Risk created an image of American public education as “mediocre,” and warned about the harsh consequences our country would face if there weren’t an educational reform. The report was in large-part a response to declining SAT and ACT scores, economic anxieties fueled by concerns about the preparedness of our future workforce, and a perceived decline in traditional values such as work ethic, discipline, and respect for authority. The report recommended all levels of education adopt more rigorous and measurable standards and higher expectations for student achievement. This led to a budgetary emphasis on academic rigor and standardized testing in core subjects, leaving most schools reducing and in some cases completely eliminating physical education programs. While it should be noted that A Nation at Risk did not make any recommendation specific to physical education, the field of physical education followed in its implementation of educational standards. It’s important to note that this report led teachers in public education to develop evidence-based practices and curriculum models from research-backed instructional material. Spawned from the educational reform, formalized standards have grown to define what students should be able to know and do in physical education from federal level reform agenda to the state level.

“The standards-based reforms and accountability movement developed as an offshoot of the original ‘systems’ reform initiative. Specifically, as the federal government became increasingly involved in setting education reform agendas on a national level, the term standards-based reforms was used to refer to ways in which individual states responded to the push for higher standards and school accountability.” Chatterji, 2002.

The increased scrutiny physical education faced after the “A Nation at Risk” report came out prompted a need for physical education programs to demonstrate their value and contribution toward student academic achievement. With physical education fighting for its existence in an educational landscape of pressure and competing priorities, the field of physical education addressed these challenges by creating the first National Physical Education Standards in 1994 (more on this in the next chapter). Because of the demand for more research-backed programming in all subject areas, the field of physical education saw a boom in research efforts. As research grew, evidence-based practices and data started showing the multifaceted benefits of high qualityhigh-quality physical education programs in the cognitive, social, and emotional development of a child. Research at this time also raised concern about the prevalence of childhood obesity and the dangers of a sedentary lifestyle.

By the end of the 20th century, advancements in motion capture technology and electromyography helped improve our understanding of motor learning processes by allowing an in-depth analysis of movement patterns and muscle activation. This improvement led to further refining of how we approach physical education. The advancement of this technology has continued to provide valuable insights into how our bodies respond to a variety of physical activities, influenced pedagogy, and assessment practices designed to promote health and motor skill acquisition.

In 2004, NASPE revised and published the second set of national physical education standards. In the four years leading up to this new set of standards, the research on the benefits of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) intensified with studies demonstrating its effectiveness in improving fitness and cognitive functioning. Due to the rise in public concern for childhood health and the research on MVPA, NASPE officially adopted the core recommendation for effective physical education programs should have at least 50% MVPA in every lesson. This marked the solidification of PE 2.0 seeing the physical educator as personal trainer where a prioritization of getting your students moving and sweating for the majority of your lesson became the expectation.

By 2010, the childhood obesity rates gained significant public attention which led to initiatives like the “Let’s Move!” campaign launched by First Lady Michelle Obama. During this time, increased research on the connection of physical activity, cardiovascular health, and overall wellness laid a foundational basis for physical education’s role in promoting lifelong physical activity habits. With many community engagement opportunities and corporate partnerships, the “Let’s Move!” campaign not only promoted physical activity through grants for physical education and after school programs, but it also implemented policy geared toward improving the nutritional value of school lunch with the “Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act.” While critics argue the campaign lacked sustainable long-term strategies for fighting childhood obesity, it did increase awareness by advocating and creating more physical activity opportunities in and outside of the regular school day.

AAPHERD underwent major restructuring and one of the major branches focused on physical education and movement science became the independent, “Society of Health and Physical Educators or SHAPE America. While the third set of national physical education standards were published in 2013, the AAHPERD leadership team was already involved with the development and rollout of the standards for many years. Even though this name change marked the end of AHPERD, individual states chose to retain their original names like the CAHPERD in California.

The National Physical Activity Plan in the United States came to fruition in 2010 in response to the federal government-sponsored U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. The National Physical Activity Plan currently includes ten sectors that include business and industry, community recreation fitness, and parks, education, faith-based settings, healthcare, mass media, military settings, public health, sport, and transportation, land use and community design. Greenberg et al. 2024 JOPERD The Role of Physical Education Within the National Physical Activity Plan.

In the early 2010s, the proliferation of smartphones and the launch of platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and later TikTok introduced new avenues for social comparison and online social interactions for students. As the age of smartphone ownership got younger and younger, and the access to social media in their pockets, excessive social media use increased dramatically. By 2015, studies began to highlight the negative consequences of excessive social media use, including increased rates of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances.

During the height of the COVID pandemic in 2020, many schools went to remote learning which heightened the emphasis on social and emotional learning to address students’ mental wellness. This shifted the need for physical education to go beyond the traditional ways of teaching content. Many physical educators were forced to reexamine how they approach the curriculum and measure learning outcomes as education had to go online.

Article assisted by John Kruse